Is Your Honey Organic?

Pop quiz: how many of the following statements apply to you?

You buy organic produce. You seek out free-trade, non-GMO products whenever possible. You don’t mind paying a few extra dollars for free-range beef or cage-free eggs. You make an effort to shop local.

If you answered yes to any of these questions, why do you make these choices? Probably because you care deeply about what goes into your and your family’s bodies. You most likely want to ensure the people responsible for growing, picking, and preparing your food are paid and treated fairly. You almost certainly prioritize the humane treatment of animals before they become your supper.

Is your honey organic? Does it matter?

One more question: is your choice of honey organic? You may be shocked to learn that this is one time that “organic” perhaps shouldn’t be at the top of your checklist.

First, a little honey bomb of knowledge: the USDA does not currently have any officially approved USDA organic honey standards. (A draft of a recommended standard was presented by the National Organic Standards Board in October of 2010, but it has not been adopted by the USDA.) But, you say, “I’ve seen the ‘USDA organic’ green sticker on jars in the store!”

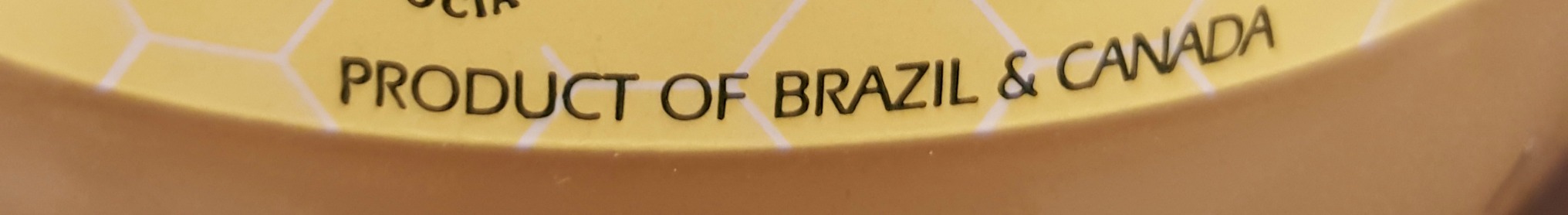

Chances are high that the USDA organic honey you see is not even produced in this country. How does that work? Well, the USDA allows its label to be used on products that meet the organic standards of the country of origin. Next time you see the USDA green sticker, I challenge you to flip that jar around. Chances are high that the honey was either produced in Mexico, Canada, or Brazil. (I recently performed a small unscientific test at my local Whole Foods. All three honeys labeled as USDA organic on the shelf were produced outside of the United States — including the Whole Foods brand.) So much for buying local. Further, even if the honey is produced in this country, the labeling and adulteration of honey is infamously egregious. Adulteration refers to the mixing of honey with another inferior and inexpensive product. Who’s excited about a bit of high fructose corn syrup with their honey?!

Country of origin on label of the same USDA organic honey pictured above.

Without a USDA standard and accompanied enforcement, I wouldn’t place much merit on that little green sticker.

Finally, it’s important to note that bees aren’t livestock that can be kept in a pen and whose movements we can control. Any organic standard would have to apply to not only the practices kept by the beekeeper in controlling pests and disease, but also what flowers the bees are visiting for feed. Did you know bees will forage up to 3–5 miles in any direction, as necessary, to find food? That means in order for a honey to be indisputably organic, the bees would have to be raised on a plot of 100 square miles of certified organic land. That is equivalent to approximately 48,400 football fields — including end zones!

Here’s the takeaway: organic honey may not be worth the sticker it’s printed on.

But wait! Just because I’ve encouraged you to look past the organic label doesn’t mean there aren’t other standards and criteria I recommend you seek that are much more important than the ‘organic’ name we’ve all grown to love. So what should you look for?

Here’s the short answer: Know your beekeeper. Research, and ask questions if need be. How does he or she prioritize the health of the honeybees over honey production? What practices does he employ to help fight disease and pests? Keep in mind that anything going into the hive has the potential to not only end up on your plate, but also affects the health of the honeybees as well.

The long answer: “Natural” beekeeping is a term that beeks (that’s beekeepers+geeks) have coined to describe practices ensuring the health and well-being of the bees are first and foremost. Those practices include, but are not limited to:

- refraining from using any pesticides or other treatments not naturally derived from entering the hives

- ensuring apiaries only contain as many bees as can be supported by the nectar and pollen supply

- refraining from using paint and other chemicals inside the hive

- only providing the bees with supplemental feed if the well-being of the honeybees is dependent upon it, rather than to boost honey production. And if supplemental feeding is required, high fructose corn syrup should never be used. (Unfortunately this is very common in large-scale commercial beekeeping.)

Thankfully there are lots of smaller-scale commercial operations that utilize these practices, and you can be assured these practices, and more, are how we choose to keep our bees here at Two Hives Honey.

Bottom line: Know your beek! I encourage you to visit farmer’s markets to buy honey from your local beekeepers. When you do, be sure to ask informed questions. I am certain they will thank you for supporting their local business! Double-win!

Check out our new online shop for when you aren’t able to make it to the market!

Great content! Super high-quality! Keep it up! 🙂

Thank you! We are glad you enjoyed this blog. Let us know if you have any blogs that you would find helpful!

Keep working ,remarkable job!

Hi Verena, Thank you!

I truly appreciate this post. I¡¦ve been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You have made my day! Thanks again

Hi Alva,

You’re welcome! Glad we could help.